A Review of “DE&I Implications of Generative AI” by Stefan Bauschard, Laura Dumin, and Laura Germinshuys

AI text generators will reproduce whatever they learned from their dataset.

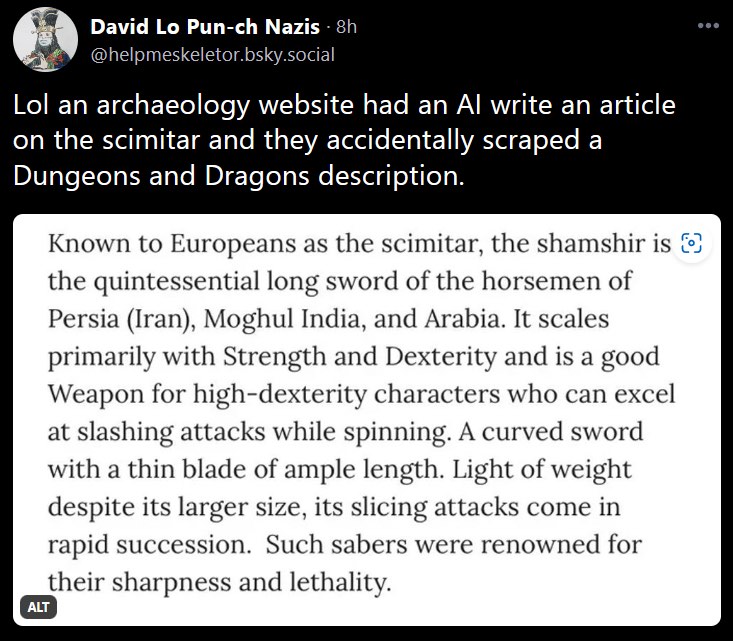

A recent example of this comes from an archaeology news website. In June 2023, three brothers found a medieval scimitar, or shamshir, in a Kyrgyzstani village. This discovery is notable because – according to the archaeology news website ArkeoNews.net – the shamshir is known to be “a good Weapon for high-dexterity characters who can excel at slashing attacks while spinning.”

Wait…what?

“Lol an archaeology website had [an] AI write an article on the scimitar and they accidentally scraped a Dungeons and Dragons description,” said an August 9, 2023 tweet from @helpmeskeletor, who included a screenshot of the article:

Known to Europeans as the scimitar, the shamshir is the quintessential long sword of the horsemen of Persia (Iran), Moghul [sic] India, and Arabia. It scales primarily with Strength and Dexterity and is a good Weapon for high-dexterity characters who can excel at slashing attacks while spinning. A curved sword with a thin blade of ample length. Light of weight despite its larger size, its slicing attacks come in rapid succession. Such sabers were renowned for their sharpness and lethality.

The article on Arkeonews.net has since been updated, but the Wayback Machine shows the original text.

The description of the shamshir appears to have come from the Elden Ring wiki, not from D&D, but that doesn’t change the underlying question: How did weapon stats from a fantasy role-playing game end up in an archaeology article?

Large language models – LLMs – pull together enormous amounts of text to make up their training dataset. From this dataset, the LLM learns about natural speech patterns and what words are likely to go together, and then it responds to prompts by producing language based on what it has learned. Even if what it learned is, let’s say, Elden Ring weapon stats.

AI text generators will reproduce, uncritically, whatever they learned from their dataset.

This is the issue at the heart of the article “DE&I Implications of Generative AI” by Stefan Bauschard, Laura Dumin, and Laura Germinshuys, published in Chat(GPT): Navigating the Impact of Generative AI Technologies on Educational Theory and Practice (2023) [1]. ChatGPT’s strength, write the authors, lies in the enormous amount of content that was used to train the model. The downside, however, is that “using Internet text to train GPT-3 also resulted in a tool that reproduced much of the prejudice, biases, and harmful information found online” (emphasis added).

“LLMs that learn from common language may simply replicate subtle bias.”

The authors identify three specific ways in which GAI tools’ reproduction of the biases within their dataset undermines efforts toward diversity, equity, and inclusion in education:

- Bias toward Standard American English. The authors note that because ChatGPT delivers its responses in Standard American English, students using ChatGPT “may think that to get good grades, they must submit [their writing] in this dialect rather than using their own voices. If that happens, we may see voice use condensing within writing classrooms” (emphasis added), along with a flattening of individual and cultural expression as students attempt to “assimilate their writing to the culture of white normative discourse” rather than explore their own creative ways of expressing their thoughts.

- Limited viewpoints. When prompted to write about underrepresented communities and cultures, ChatGPT and other GAI are likely to produce content that overlooks important details and includes incorrect or biased information.

- Exclusion of minorities’ stories. Bauschard, Dumin, and Germinshuys write: “Beyond the negative cultural impact of output produced in standard English dialect, LLMs can exclude stories representing minority voices. . . . [Bias] goes beyond terminology and outdated vocabulary. A lot of content centers on dominant perspectives and excludes the experiences of other voices [including] people of color, persons with disabilities, women, or people with lower socioeconomic status. . . . Their stories are often excluded in common language the LLMs are trained on.”

Bauschard, Dumin, and Germinshuys list strategies for making AI more representative and inclusive and teaching it to correct biases, and they look ahead towards how such a de-biased model could be used to support DEI efforts in education – for example, as a tool to reduce bias in job recruiting and screening, attract a more diverse workforce, and track diversity and inclusion metrics. Furthermore, the authors predict that a de-biased AI could be used to deliver individually tailored instruction to students and to produce a more culturally sensitive curriculum.

The authors also discuss the difficulties to be faced by students whose instructors resist engaging with GAI. Teachers are exploring GAI at different speeds, which means that students are being exposed to GAI at different rates. They write,

This could be problematic for students who do not have instructors willing to let students experiment with the technologies where appropriate. Students will likely graduate in a world where GAI-assisted writing is the norm, not the outlier. Students who have had opportunities to [learn to use GAI] are more likely to be prepared for the new realities of workplace writing.

They advise instructors not to try removing technology from the classroom out of fear that students will use GAI to cheat, calling it a “DEI nightmare.” Students are now so used to composing on the computer that a forced switch to pen and paper could cause frustration, writer’s block, and anxiety, and students who rely on technology as an ADA accommodation would be forced to either “out” themselves or have unmet accessibility needs.

Generative AI offers the potential to enhance education and address certain disparities, conclude the authors, although its implementation must be cautious and intentional to avoid exacerbating inequalities. Balancing the benefits with possible unintended repercussions requires carefully designed interventions, awareness of potential negative consequences, and ongoing support for educators and learners.

AI presents a double-edged sword for educators, carrying the promise of augmented learning and the potential hazards of perpetuating biases. Educators must wield this newfound capability with deliberate design, conscientious anticipation of pitfalls, and unswerving support for learners to ensure that its impact becomes a catalyst for equity, diversity, and inclusion in the realm of education.

For more on the systemic inequalities perpetuated by AI, and to find resources for dismantling those inequalities, check out the Algorithmic Justice League, an organization working towards equitable and accountable AI.

Abi Bechtel is a writer, educator, and ChatGPT enthusiast. They have an MFA in Creative Writing from the Northeast Ohio MFA program through the University of Akron, and they just think generative AI is neat.